Botnahytto 75-years Remembrance

Remembrance of a rescue mission in Os 75 years ago

1944 2019

A CANADIAN CREW OF SIX SURVIVED EMERGENCY-LANDING, WAS RESCUED AND RETURNED TO ENGLAND.

A remarkable wartime rescue operation took place in Os, Samnanger and

Austevoll 75 years ago.

The story of the events is a read exciting as a crime novel, dramatic, but sans any bloodshed – and it has a happy ending. A large allied warplane with six men made a critical emergency landing on land, in Haugland, Os; a location where no one would think survival was likely – with great German forces all around them. Though everything pointed to things ending badly, the six Canadian men were safely back in England, unharmed, less than three weeks after the emergency landing.

A well-known film director is now planning to turn the story of these events into a movie.

Emergency landing in German-occupied land.

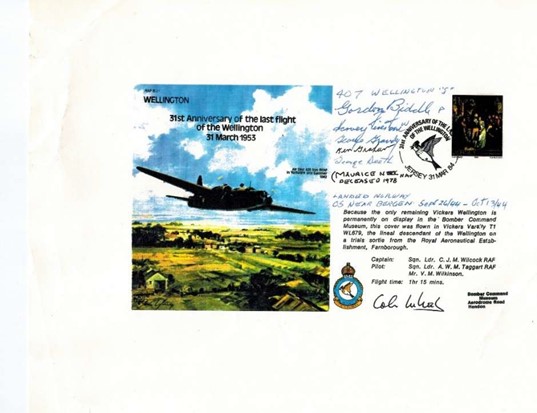

A two-engined Wellington aircraft from the Canadian Air Force in England, was searching for German submarines across the North Sea, early in the morning on September 26, 1944. With one of their engines on fire, they tried throwing out all unnecessary equipment, mines and fuel to ease the plane. It was not enough to make a return to England feasible, and they opted instead to head for the Norwegian coast.

As they were coming in over Os from the west, making a turn over Sandholmane towards Hatvik, they were still losing altitude – and then the second and final engine stopped working. Captain Gordon Biddle was forced to make an emergency landing in the terrain that lay beneath them, uneven as it was – with both hills and small valleys cutting across; Baggane, at Søre Neset.

On the way down the plane cut a high voltage line to Halhjem, Haugland and Lunde. The left wing cut several thick trees at a height of 1.5 meters, right next to the house at Baggane. Then one wing touched the ground, turning the plane around ninety degrees; before the tail part touched down; and finally the front part.

In this way Gordon Biddle managed to land and stop with a «landing strip» of only 20-25 meters.

Pilots who have later seen the site of the landing, find it hard to even imagine it possible.

The crew not only survived the landing, but for some minor cuts and bruises, they were largely unharmed.

The Canadian airmen climbed out of the plane, as people from the nearby farmhouses were coming to see what had happened. Very few of the locals spoke any English.

Away from the landing site.

The plane landed not far from the old school house on Søre Neset, and the Canadians happened to meet the teacher Magnus Askvik, one of the few there who could speak English. He explained to the airmen where they were, and gave them directions to Bjørnen, so they could get away from the site. At that time there was no road to Bjørnen.

The six started out through the woods, hiding some of the military clothing and washing their wounds on the way. Arriving at Bjørnen, they met Marta Bruarøy and Ingeborg Bjørnen. Marta took the airmen up into the forest to a small cave, instructing them to hide there until they heard more. Later, the women returned, bringing them food and something warm to drink.

One of the people noticing the unusual aircraft movements this morning, was Einar Evensen, on Bjørnarøy. Realizing that the plane was bound to have hit the ground in some way, and there having been no sound of an explosion nor sign of a big fire, he thought there may be survivors. He tried to get information on what had happened, but found out very little.

When Einar returned home, Ingeborg’s father, Hans Bjørnen, was already there. Hans told them what had happened in Bjørnen.

Being very keen on helping the Canadians, he wanted to know if Einar could take them over to Shetland with his motor boat. Einar told him that his boat was in no shape for such an endeavor, but that he would sort out how to take care of the six.

It was arranged so that Ingeborg Bjørnen and Johannes Ferstadvoll, who spoke English, went to the Canadians that same evening. In complete darkness and through difficult terrain, the airmen were moved from the cave to Trynevika, at the end of Bjørnatrynet. Einar Evensen and his helpers then took over the charge.

With sacking around the oars.

There were German cannon positions at Røttingo, as well as a lot of German navy boats in the area, so the Canadians were shipped in Oselvar rowing boats, with sacking around both the oars and the oarlocks to muffle any noise.

The rowers were skilled and the voayage went on silently. When they reached the bridge over the narrow strait between Bruarøy and Vedholmen, people were sent on shore to make sure there were no Germans on the road or on the bridge that might see them.

Those taking part with Einar on this were: Torvald Jakobsen, Magnus K. Røttingen, Hans Holmefjord and Nils Røttingen. Nils had been in America, and had the important task of interpreting.

The airmen were put ashore in Selvågen in Sørstrøno and were housed in a summer house, with a German garrison facing them on the other side of a narrow strait – at Røttingatongane. The house itself was being used by a German commander, but he was in Germany on leave at the time when this happened.

They were at Strøno for 4 days, as Milorg in Os was planning the next steps to the rescue operation.

They spent their nights inside the house, and their days hiding under a tarpaulin up in the forest, towards Husfjellet.

The Germans searched Os intensively, looking for the Canadians, but did not arrive at Haugland until a couple of hours after the emergency landing. By then the airmen were gone and the locals had had some time to sort out what to say. An old wife who was questioned by the Germans told them she had indeed seen some men, but that they had gone on to the main road. “They might have taken the bus”, she said. The German’s interrogations were rough and severe, but did not provide them with any useful information.

On the quay at Halhjem, where the ferry quay is now, there was usually a German guard force posted. This day there was a change of crew at the post, and therefore reduced preparedness. The Germans searched around almost everywhere, with very few exceptions; one of them being the Summer house and the area surrounding it – the very place the Canadians were hiding.

Many years after the war, one of the Canadians randomly happened to run into and got to talking with a German who had been stationed in Bergen during the war. The man had been part of the search for the Canadians, and told him there had been as many as 4000 German soldiers out looking for them. At the time, in 1944, the whole municipality of Os had a population of roughly 3000 people.

Moving to Lønningdal, Øvredal and Botnahytta.

Einar Evensen contacted key people in Milorg in Os, with Jakob Hjelle, Magnus Hauge and Johan Viken at the forefront.

It was decided that the six should be moved to Lønningdal, and from there to go by way of Øvredal to Botnahytta, a cabin in use by Milorg. Fredrik Øvredal built this cabin in the mountains between Os and Samnanger in 1942, as a hunting lodge (the cottage lies in Samnanger). Here, the Canadians could be kept out of harm’s way, awaiting the arrangement of transportation across the North Sea.

All this went on in the last year of the war, when almost everything was in scarce supply.

There was strict rationing and little to get hold of, even with ration cards. Getting food for six young men extra was no simple matter. It was mostly from their own homes, and from Anna and Nils Rolvsvåg in Rolvsvåg, that the helpers got the supplies they needed.

The overall situation did not make it easy to have six foreigners in uniform lying in cover. It was difficult to move them over long distances. In Os, with all the fortifications, the Ulven camp and the submarine training base in Hatvik, there were Germans everywhere. German raids and searches could come at all times. A special license was required to travel, and all had to carry a passport – a Grenzzonebescheiningung – on their person at all times. All phone calls might be intercepted by the Germans. The Gestapo had their spies out, and one could never trust people one did not know; and not necessarily people you did know, either.

There were few means of transportation available; bicycles on land and rowing boats at sea were the norm. There was no bridge to the Søre Øyane or Strøno islands, and the valley of Øvredal was roadless.

«Six sacks of potatoes».

On a sunny Sunday, October 1, 1944 – they started on the trip from Sørstrøno to Lønningdal. They used Evensen’s boat, rigged as a boat fishing for tuna. Three men were visible – Evensen, Jakobsen and Biddle. The other five lay on the deck under a tarpaulin. The trip went first across the fjord towards Vinnes. A German patrol boat heading their way created great excitement for a while, but it changed its course after investigating the fishing boat through binoculars.

They made a brief stop at Skjørsand for Evensen to telephone one of his contacts to let him know that he was on his way to Lønningdal with «six sacks of potatoes»

The Botnahytto cabin in 2018, after the restoration.

The Milorg-men Jakob Hjelle and Haldor Øvredal (Milorg/Saborg), as well as Linge-man Helen Mowinckel Nilsen received the Canadians at Lønningdal.

They had sentries scouting for Germans posted all around the rendezvous. In Lønningdal, the Canadians were fed a hot meal by Marta Øvredal, before being rowed across Øvredalsvatnet. From here, they went into the valley, up

Baggjeskaret and to the cabin Botnahytta, where Ivar Dyngeland received them. In this cabin the airmen got to rest up, and even enjoyed some peaceful days.

Botnane resembles the area in Ontario where some of the Canadians came from, so they called the place «Little Canada”.

The name was in part inspired by the training center for Norwegian airmen in Canada during the war, which was called «Little Norway».

Kjell Harmens was in hiding at Lønningdal, and from there he relayed food and messages to them by foot, and also served as an interpreter. Rolf (Piten) Olsen was in hiding in Rolvsvåg. From there, he functioned as a sentry – in addition to bringing in food and messages to the cabin. Torbjørn (Tobben) Lyssand had a lot to do with the setup of things for the airmen at Lønningdal and in Øvredal, together with Jakob Hjelle, Haldor Øvredal and Helen M. Nilsen.

A few misunderstandings, as well as due caution in the radio communications between Norway and England, delayed further developments. But then one evening came the special report over the radio, to «keep the meatballs warm», which meant that the Canadian airmen were to be ready to be picked up in Austevoll two days later.

Back to England.

On the evening of October 9th, the Canadians and the Norwegian helpers went down to Øvredalen. They had some food at Ida and Nils Øvredal’s place, and continued with a rowing boat to Lønningdal, where they were placed in a boathouse in Bjørndalen.

At noon on October 10, Lars Orrebakken came with the motor boat «Snøgg», took on board the six Canadians and Haldor Øvredal, and started out the fjord. There were many German watchboats on the fjord and submarines from the submarine harbor in Hatvik, but «Snøgg» went steady on towards Vinneslandet. Outside Hatvik, the Canadian navigator Neil wanted to get up on deck and make note of the position; he wanted to return later to bomb the submarine harbor, but Haldor got him back down in the cabin.

After a trip into a bay on the north side of Tysnes, they continued to Ospøy in Austevoll. Here they met Einar Evensen who wanted to say goodbye to the Canadians. He had also brought with him another man, who was going over to England with them.

From Ospøy, Sverre Østervold transported them over to another island, Kjøpmannsholmen, where there was an old boathouse. Here all seven men set for England were told to wait.

A boat from Shetland was to come over and pick them up that same evening – two weeks after their emergency landing. Due to bad weather conditions, however, the pick up was delayed. It took three days until they finally received the message “we walk on rubber soles” – which meant that Leif Larsen – “Shetlands-Larsen”, with Harald Drønen as a local guide from Austevoll in his crew, were picking them up in Følesvågen, with “Vigra”, a submarine hunter.

«Shetlands-Larsen» brought them safely across the North Sea to Shetland.

Haldor Øvredal told us that when the message «it rains in the mountains» was broadcast on the BBC special broadcast the next day, most things came to a stop for a few second – in Os, Samnanger and Austevoll. The coded message relayed the incredible news that the Canadian airmen had arrived safely in England.

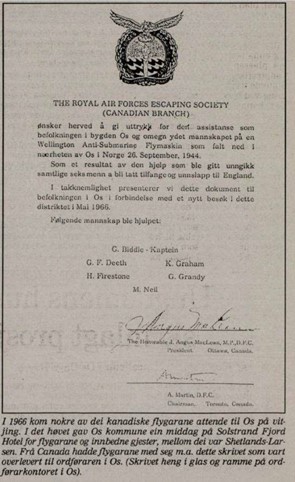

Many years later, some of the helpers from Os were on a tour to Canada, commemorating what happened in the fall of 1944. One of the Canadian speakers informed that this was the only time during the Second World War that everybody in such a large crew came safely and unharmed home from an emergency landing in German occupied country. It was with great pleasure that the Norwegian veterans heard this.

The Germans never did find out who had helped the Canadian airmen get out. The raids, searches and torturing that took place in Os later in the Fall of 1944, was unrelated to the events surrounding the Canadians and their rescue.

The first picture on page 1 is taken at Botnahytta in 1944, it shows from the left: Jakob Hjelle, Thorbjørn (Tobben) Lyssand, Kjell Harmens (still alive in 2019), Ivar Dyngeland, Haldor (Sigvald) Øvredal and Rolf (Piten) Olsen.

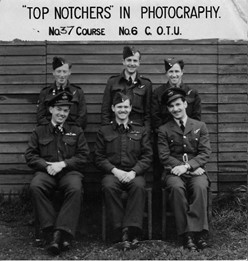

The second picture shows the Canadian airmen, during training in England. From left behind: Harvey Firestone (still alive in 2019), Ken Graham, George Grandy

Front left: George Deeth, Gordon Biddle, Maurice Neil.

The picture shows from behind: Haldor Øvredal, Lars Orrebakken, Torbjørn (Tobben Lyssand), Sverre Østervold, Magnus Hauge, Harvey Firestone, Einar Evensen. From the front: Jakob Hjelle, Henrik Lyssand, Marta Bruarøy, Ingeborg Bjørnen, Hanna Bjørnen, Magnus K. Røttingen and Helen Mowinckel Nilsen.

Sources:

Conversations with Einar Evensen, Jakob Hjelle, Haldor Øvredal and Arthur Lunde.

Harvey Firestone: «Six sacks of potatoes» Kjell Harmens’ notes.

Arnfinn Haga’s books: «It is raining in the mountains» and «Emergency landing». Finn Dyngvold and Trond Hagenes: «A small island society in the big war 1939-1945»

This memo:

Gustav Moberg in 1994, 2004 and Bjarne Øvredal in 2019. English translation in 2019: Marius Hjelle.

Os Sogelag